A new pattern of global disease circulation has been identified by scientists, which has already been observed in countries neighboring Brazil.

Scientists suggest that alterations in birds’ migratory patterns and their natural habitats are among the potential factors behind the emergence of new disease distribution patterns.

Over the past century, there have been recurrent occurrences of outbreaks in domesticated birds, particularly chickens bred for human consumption in Asia, Europe, and Africa.

Measures such as culling can help prevent transmission to other species, which could potentially disseminate the virus globally and reintroduce it to domesticated birds.

Scientists have noted that in recent years, the virus responsible for bird flu has been circulating differently. There have been sporadic outbreaks of the disease on nearly every continent, often occurring during atypical periods when it is seldom detected.

Jean-Pierre Vaillancourt, a professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences at the University of Montreal, questioned in an interview with Grist how it is possible for a virus to appear during the summer in the Mediterranean Sea or on a Canadian farm during temperatures as low as minus 20 or 30 degrees Celsius.

According to experts, nearly 80 countries worldwide are experiencing this issue, which is unprecedented. Along with shifts in migratory patterns, the decline in biodiversity in certain regions could cause birds to settle and reproduce in locations where they are more likely to come into contact with domesticated animals.

Closer And Closer

Even though the affected animals in these two countries were wild birds, Brazil’s Minister of Agriculture and Livestock, Carlos Fávaro, cautioned that the country is heightening its monitoring efforts and implementing additional preventive measures. Last week, three potential cases were examined in Brazil, but the results were negative. Brazil, the world’s biggest chicken exporter, shipped out a record-breaking 4.8 million tonnes of chicken last year. The United States faced losses of around 50 million birds due to the disease or culling last year, while the United Kingdom, France, and Japan also experienced unprecedented losses in 2022.

Is a new pandemic on the horizon? The factors that are altering the worldwide distribution of bird flu could also contribute to the increase in mammalian cases of the disease, potentially posing a health threat to humans.

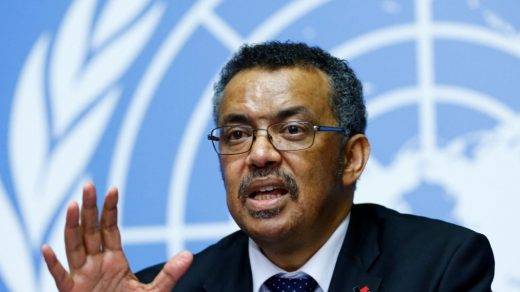

In early February, Tedros Ghebreyesus, the director of the World Health Organization, warned that the global community must brace itself for a potential human avian flu pandemic.

In theory, the situation is reminiscent of the one that gave rise to the Covid-19 pandemic: the virus making a “leap” from one species to another. Incidences of H5N1 infection have been documented among various mammalian species, including sea lions in Peru, martens in Spain, and foxes in England. However, there is presently no indication that the virus will undergo a mutation that could infect humans and, crucially, spread from person to person.

Although the World Health Organization (WHO) considers the likelihood of a new pandemic to be low, experts are concerned about the spread of cases across multiple regions, particularly in the Americas, and the potential for direct transmission of the virus between mammals, given the constant mutation of viruses.

In the event that the disease spreads to humans, which typically occurs through direct contact with infected birds, the mortality rate is exceedingly high, at approximately 50%, according to the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control.

The current strain of the virus is infecting a broader range of species than its predecessors, including some that do not migrate over long distances. This could help to explain why the disease is persisting during unexpected times.

As the disease becomes more widespread, the likelihood of dangerous mutations increases.